Robert Bakewell

The Shorthorn breed had taken form by the late 18th century with the earliest representatives reaching the shores of Virginia as early as 1783. This was achieved with the application of breeding principles initially developed by Robert Bakewell, the recognized “Father of Animal Breeding.” His methods of carefully selecting foundation stock of desired type and then using a well-defined system of breeding “like to like” regardless of relationship (linebreeding/inbreeding) could create a group of similar individuals that were fixed in type and would breed true. Stock belonging to “breeds” created using this breeding method then could have economic value. These principles had created in the fledgling Shorthorn breed… cattle which could contribute increased growth for production of beef, add scale to the local cattle strains for use as work oxen, as well as improve the ability to fatten and increase milk production. By the early 1800s these useful traits combined with strong promotional efforts in exhibits and sales made Shorthorns popular and well recognized throughout Great Britain, Continental Europe, and North America.

At this time in Great Britain, much of a person’s position in life was determined by their social class and heritage. A small portion of the population which included the British nobility and a British social class referred to as the “landed gentry” owned a major portion of the land. They could live entirely on rental income or at least had a country estate. Land ownership would be passed on through generations. This system also prompted the issuance of many long-term leases which could also be passed on to succeeding generations. Those who held these leases were still referred to as “tenant farmers” but had control over large tracts of land with many employees. This social system with the importance of family lineage was certainly a driving force behind the establishment of a herdbook for the Shorthorn breed. This maintenance of records and documentation of ancestry was an important step in their improvement and expansion.

The first herdbook for any livestock species to be published in Great Britain was The General Stud Book for Thoroughbred horses first printed in 1793. Its intended purpose was to be a public registry system for pedigrees to identify those horses that qualified for specific races. Although slightly different in their intentions from the General Stud Book, the first cattle breed herdbook published in the British Isles was for Shorthorns. In 1812 a meeting was held including respected Shorthorn breeders Sir Henry Vane Tempest, Col. Totter, and George Coates to discuss the publishing of a herdbook. These same breeders met later that Fall in a second meeting which included several more prominent Shorthorn breeders. Among those present were members of the Colling family, the Booth family and Thomas Bates, all who had already figured prominently in the founding and expansion of the breed. All those in attendance endorsed the idea of a herdbook and since many of these Shorthorn breeders also raised horses, they looked to The General Stud Book as a model.

The attendees also agreed that George Coates was the person to gather the information and lead the task as editor. It was believed that he was fitted for the duty by his large knowledge of pedigrees, great interest in the cattle, knowledge of the breeders and confidence they placed in him. Sir Henry Vane Tempest who had extensive land holdings and coal mines in northeast England agreed to offset the expenses of gathering the data and printing the book.

Coates immediately got to work on the project, only to be stymied nine months later with the unexpected death of Tempest. Although, the loss of “Sir Henry” delayed the project indefinitely, Coates continued his work of gathering data that would one day be needed to publish a herdbook. Alvin Sanders described Coates’ work in his book, Red, White, and Roan: “This difficult task was successfully undertaken by a well-known character of his day and generation, old George Coates, who rode up and down the valley year after year in quest of necessary data. His familiar figure, old white nag and saddle bags, traversing the highways and by-ways of that historic region. Coates also attended the “fairs” or market days, held at Yarn and Darlington and other points, where the Shorthorn fathers were wont to gather to exchange views and discuss ways and means of promoting improvement in the local cattle stock.”

Sir Henry Vane Tempest

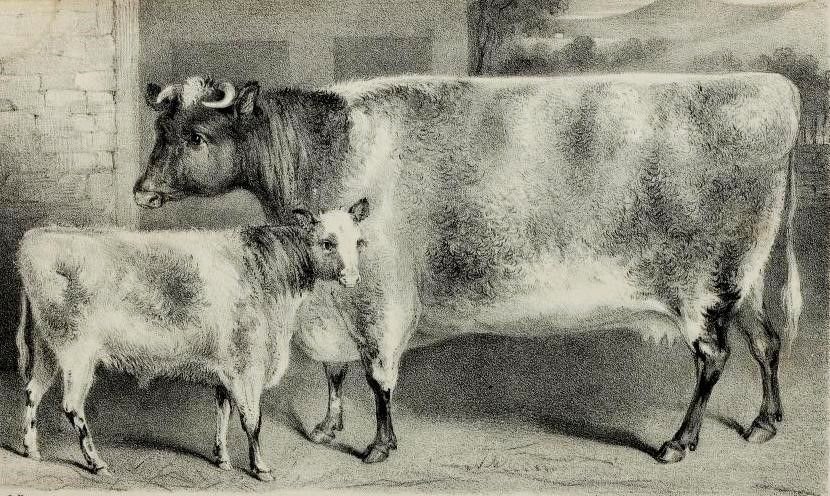

“Fashion” and a calf, bred by Sir Henry Vane Tempest

Another gathering of Shorthorn leaders occurred after Robert Colling’s sale in 1818. Printing of the book had remained on hold, but it was decided to move forward with the project. Robert Colling and Jonas Whitaker agreed to defer the expenses to print the book. Their money would then be recouped through subscriptions. However, Colling died in March 1820, which further delayed the project for lack of funds. After these delays, in 1822 Whitaker, who had become a large breeder and a leader in exporting cattle to America advanced the monies necessary to publish Shorthorn’s first herdbook. The book got printed in the autumn of 1822 with 505 subscriptions, at a guinea each per book paid on delivery for a total of $2,525. At this subscription cost, it was reported that it was not a profitable enterprise for Coates.

The first edition contained entries on 710 bulls, with about an equal number of cows. The early herdbooks sometimes had meager pedigrees because the ancestry of many foundation animals was unknown. Coates had to depend on information from private herd records, which were frequently “sketchy,” and simple recollections and stories of many years distant from people who lived during those times. The earliest birthdate of an entry into this edition was the red and white Studley Bull (626) calved in 1737. Bulls and cows were cataloged separately. Bulls were assigned a registration number and arranged alphabetically by their name. Cows were not given a registration number and were cataloged alphabetically by name with some of their progeny listed below. In reference, cows were identified by the herdbook volume and page number where they were listed, ie. (Lavina v.1, p. 373). Bulls and cows were cataloged separately until well into the 20th century. It was published under the title The General Short-Horned Herd-Book: Containing the Pedigrees of Short-Horned Bulls, Cows & c. of the Improved Durham Breed. It became known as the Coates Herdbook and still bears this name today. As future books were published, the pedigrees could be traced back through the various editions.

As indicated, the first editor of the Shorthorn herdbook, George Coates, was also an early breeder of Shorthorn cattle. Unlike many of his contemporaries involved with the formation of the breed, Coates was not a man of means. Still, it would be Coates who relentlessly undertook the monumental task of gathering pedigree information for the contents of the first Shorthorn herdbook. It appears that it had to be a “labor of love” because his compensation was very meager. After the publication of the first Coates Herdbook—which reportedly provided Coates with no renumeration—he nevertheless started collecting information for the second edition.

“Patriot” (486), bred by George Coates

The second volume would not come out until 1829, with volumes after that being edited by Coates’ son and then Henry Strafford. In 1874, the Shorthorn Society purchased the herdbook, moving it out of private hands. It is hard to find fault with anyone who worked so hard for so little financial reward as the elder Coates. Still there were some who felt that there was benefit when the society took over the herdbook.

Shorthorns were among the first breeds to be improved but also had public pedigree information that was available earlier than for any other cattle breeds. Breeders of other breeds utilized similar breeding strategies at the fountain head of their breeds, yet they had no public herdbooks until later dates. Shorthorn ancestral information was available because of the publication of the Coates Herdbook which also set a precedent to establish herdbooks for most other livestock breeds, regardless of specie. This was useful in developing expanded world-wide markets. With the obvious expense and time involved in the importation of cattle, ancestral documentation surely had significant value. This was borne out when investment trips were taken to the British Isles to secure improved cattle breeding stock in the early part of the 19th century. With no specific breed designation or preference in mind, in most cases they came back with Shorthorns that were offered to eager buyers. This coined the Shorthorns as “The Great Improvers.”

The Coates Herdbook also provided a model and information source for the American Short-Horn Herdbook to be first published in 1846. All these events, no doubt provided an important encouragement to the ultimate popularity throughout the British Isles and expansion across the globe. They became the most numerous breed in Britain, North America and Australia well into the 20th century and have had major influences as foundation stock for many other breeds.

Shorthorns have a unique history in that breeders can retrieve pedigree information as far back as the founding herdbooks of the breed. Shorthorns that trace in all ancestral lines to these herdbooks have the designation of Heritage/Native Shorthorns and are identified and promoted by The Heritage Shorthorn Society.

“Sir Thomas Fairfax”, bred by Jonas Whitaker

Author Profile: Dr. Bert Moore

Bert Moore proudly admits that he “grew up on Shorthorn milk.” Raised on a north central Iowa farm the only cattle that he knew were the red, white and roans. His first Milking Shorthorn came as a gift from his grandfather to his sister and him with the provision that they would receive every other calf and their father would receive the alternating year’s calf to pay for feed. With ten stanchions in the barn, when eleven cows were “fresh” it was Bert’s job to milk that eleventh by hand. This did not enamor him to the dairy business. Beef Shorthorns were added and comprised all his 4H projects. Shorthorns were the only breed both of his parents and both sets of grandparents raised making him a third generation Shorthorn breeder (on both sides of his pedigree).

Bert has a degree in Animal Science from Iowa State University, and MS and PhD degrees from North Dakota State University. As a faculty member at NDSU for over forty years he taught a wide variety of courses, advised students, conducted applied research and coached the livestock judging team. He has judged livestock shows from local to international levels in 29 states and 4 Canadian provinces and has given presentations in Great Britain and New Zealand. After leaving North Dakota State he served as the Executive Secretary of the American Shorthorn Association. He and his wife Millie currently live in Indianola, Iowa where they maintain a herd of Shorthorn cattle, a portion of which are Heritage Shorthorns. Because of his deep interest in beef cattle history he has amassed an extensive collection of reference materials, authored numerous articles, and co-authored a book on the history of Shorthorn cattle to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Shorthorn Association—“Shorthorn and the American Cattle Industry”.